Last updated: 11/29/23

This article will show you various research studies and other qualified OBGYN references that demonstrate exactly how a C-section cuts a person’s abdominal muscles, thereby affecting a mother’s function and recovery. This is critical information for any fitness professional to understand. It is also important for any person desiring the fastest postpartum recovery.

In addition, it is critical for both fitness professionals and birthing women to understand that the industry discussion that points women toward the idea that “no muscles are cut” is often disempowering, by directing attention away from what’s really important: function and recovery of the core muscles.

As many of you know, C-section rates are at all-time highs in hospitals around the world, and in most cases, appropriate rehabilitative therapy for this “Class Major Surgery” is practically non-existent.

Does it even matter if it’s the “muscle” that gets cut, versus the tendon of that muscle?

Those who suggest that “abdominal muscles are not cut during C-section” provide information that is incomplete, and often misleading. (By the way, doctors and others who are “educated” provide this kind of information all the time). Consider what would happen if a surgeon took a scalpel to cut across the very bottom of your calf muscles (gastroc/soleus) and suggested, “don’t worry, i’m not going to cut your calf muscles at all!” Instead, the surgeon tells you that they are going to cut only the calf “tendon” (the achilles tendon).

Should this make you feel better about the result? In other words, will your ability to walk, or even stand, be somehow better because they’ve cut the tendon, rather than the muscle itself?

Remember, the tendon is the tissue that the muscle becomes just before it attaches to the bone.

For those who’ve never had an education in anatomy and physiology, it may seem appealing to think that your muscle isn’t getting cut. However, if you are a professional who has learned about physiology, you would understand that cutting the tendon causes as much damage to one’s ability to function as would a similar cut in any particular muscle.

In fact, cutting tendons is considered worse than cutting the muscle. “Tendons generally have a more limited blood supply than muscles. This makes them somewhat slower healing structures in comparison to muscle,”[1] and “once a tendon is injured, it almost never fully recovers[2].” Oops, maybe celebrating “not cutting the muscle” is a bit premature.

And we aren’t yet taking into account the fact that the fascia – which is also being cut during a C-section – is an extraordinarily intelligent system. “Recent studies have elaborated the role of muscular fascia as [an] essential force transmitter in muscular dynamics.”[3]

Altogether, perhaps we should heed the advice from a recent (2019) Medical News Today article: “Untreated tendon and ligament injuries increase the risk of both chronic pain and secondary injuries. People should seek prompt medical care rather than ignoring the pain.”[4]

People should also start offering better advice and better treatment to our postpartum mothers who undergo C-section. There should be a standard post-operative therapy for C-section in every country whose hospitals offer this “Class Major Surgery.” Class major surgery includes operations like hip replacement and brain surgery. Just like post-op therapies for other “class major” surgeries, a C-section requires postpartum recovery core exercises and an exercise program for re-integration.

And so, even if it were technically accurate to say that “no muscles are cut”, cutting the tendon & fascia causes the same damage, if not more, to the abdominal wall.

Wasting time in this debate completely misses the important point that real therapy must be performed regardless.

How many layers are cut during a C-Section?

A C-section cuts through all layers of the abdominal wall, and multiple layers within each of these three main areas:

- Fascia (including skin)

- Tendinous Sheaths

- Muscle (abdominal muscles and uterus)

As everyone on both sides of this debate would agree, “fascia” is definitely cut during a C-section. Johns Hopkins Health defines fascia as “a thin casing of connective tissue that surrounds and holds every organ, blood vessel, bone, nerve fiber and muscle in place. The tissue does more than provide internal structure; fascia has nerves that make it almost as sensitive as skin.”[5] The resulting C-section scar tissue directly affects the muscles in that area:

- “In the region of the abdomen south of the belly button, there are two layers of fascia (continuous connective tissue) that run external to the abdominal muscles and four layers that run between and/or deep to the abdominal muscles. When the abdominal wall undergoes surgical incision, each of these fascial layers is penetrated. As the incision heals, scar tissue anchors each of the layers together, interrupting the ability of each of the muscular layers to glide over one another as they contract and relax.”[6] This is how C-section scars are formed.

According to a 2015 research study, “The choice of the type of abdominal incision performed in caesarean delivery is made chiefly on the basis of the individual surgeon’s experience and preference. A general consensus on the most appropriate surgical technique has not yet been reached…pain, due to nerve damage, seems to represent the most relevant cause of maternal postsurgical discomfort.”[7]

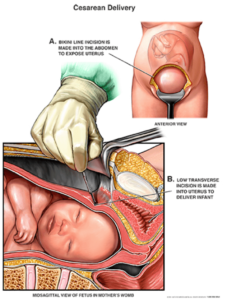

“Chapter 60: Cesarean Delivery” of Textbook called “OB/GYN Hospital Medicine: Principles and Practice” tells doctors, “Appropriate knowledge of the anterior abdominal wall is necessary to perform cesarean delivery. The layers encountered when making a low-transverse abdominal wall incision include the following:”[8]

- “The thicker rectus fascia created by the aponeurosis of the external and internal obliques and the transversus abdominis muscles”

- “The midline muscles of the anterior abdominal wall: the rectus abdominis and the pyramidalis”

You can see that not only is there a direct reference to the rectus abdominis (the “6-pack”) and pyramidalis muscles, but also to the tendon[9] portions of the external obliques, internal obliques and transverse abdominis.

Already this should put to rest any debate that questions, “Do muscles get cut during C-section?”

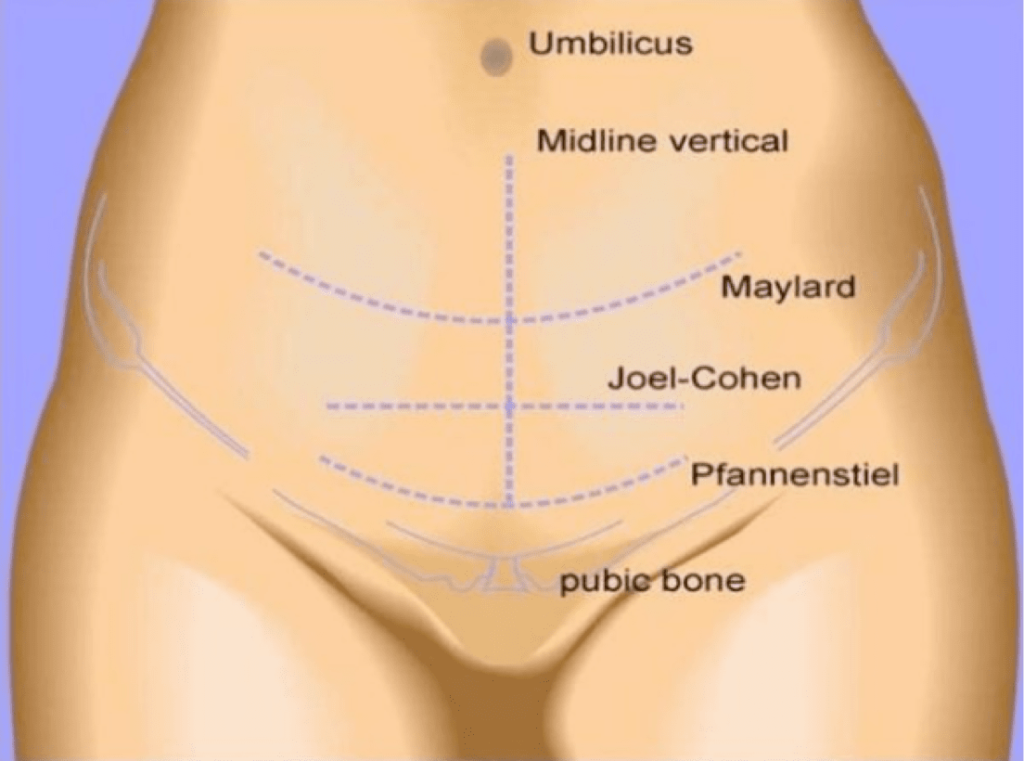

There are a couple different cuts that will initially be made for a C-section. The very lowest (and therefore possibly construed as “farthest from the abdominal muscles” is called the Pfannenstiel incision [Sounds like “Fan-An-Steil”]. As of 2010 research in Gynecological Surgery, “The preferred transverse incisions worldwide are the Pfannenstiel and the Joel-Cohen (JC) incisions.”[10] Pfannenstiel often wins because it is considered to be more cosmetically pleasing[11],[12],[13] (which does not necessarily mean that it is functionally the best way to cut through the muscles.)

The OB/GYN text states, “At the level of a low-transverse incision, the fascia entirely overlies the rectus muscles.” This once again confirms that a low horizontal cut is going to cut through layers of both fascia and muscle.

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center also confirms that the Pfannenstiel incision means that the rectus abdominis muscle is cut:

- “Layers [are] incised are as follows: skin, superficial fascia (fatty and membranous), deep fascia, anterior rectus sheath, rectus abdominis muscle, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal connective tissue, and peritoneum.”

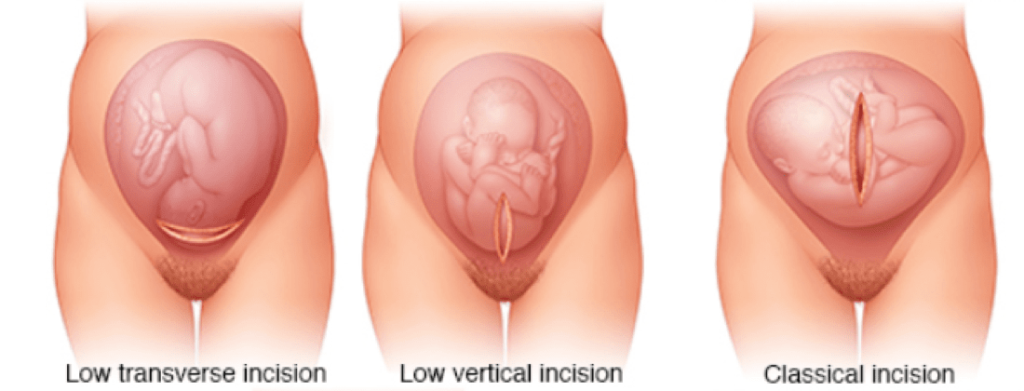

Note that all of those above layers are incised, leaving the following layer – the uterus – to be potentially given a different style of cut altogether, depending on the surgeon’s preference and discretion.

By the way, the uterus is a muscle, and the uterus is cut during a C-section. It is the muscle in which the fetus resides for 9 months. In fact, the uterus is so much of a legitimate muscle that it is often considered perhaps the strongest muscle in the human body.[18],[19],[20] By definition, a C-section cuts this muscle.

“The uterus consists of the serosal outer layer (perimetrium), the muscle layer (myometrium), and the inside mucosal layer (endometrium). All three of these layers are incised.”[21]

How did society start talking about whether or not muscle cutting is done anyway?

Research studies can be a quirky thing. It is rather common that the wording of a study gets misconstrued in the media (as well as amongst the varying online opinions). “For science reporters, new studies are irresistible — a bold new finding makes a great headline.”[22]

One of the reasons why this debate emerged may be related to how one of the most prevalent and heavily-cited studies was worded back in AJOG in 2005. In fact, this was a “review” of tons of previous scientific research, which means that these scientists sought to analyze literally everything to date, “All randomized trials that covered a surgical aspect of cesarean delivery were included in the review.”[23]

Authors wrote, “Rectus muscle cutting has been studied in 3 trials that included 313 women…These women were assigned randomly to either Maylard (muscle cutting) or Pfannenstiel (no muscle cutting) techniques.”[24]

The thing to note as to why this wording is important is that these authors were making a classification for the sake of contrasting the two different incisions (muscle-cutting vs non-muscle-cutting). They did not intend to clarify function or even the accuracy of whether the “non-muscle-cutting” group actually had perhaps the “lower portion of their muscles cut,” compared to a more “middle portion.” In other words, based upon the scientific references earlier mentioned – the ones that have already acknowledged that muscles are indeed cut – these authors’ terminology is technically incomplete, albeit perfect for clarifying the concepts intended in their 2005 review.

The main point here is that one of the most regarded C-section studies in the last couple decades decided to use terminology that suggested that “non-muscle-cutting” was an option, even though that isn’t really accurate.

For fitness professionals who are wondering, neither cut was “associated with any difference in operative morbidity, difficult deliveries, postoperative complications, or pain scores in these studies” although there was “a trend for better strength in the Pfannenstiel group.”[25] In other words, complications and pain were equal regardless of where the cut was performed, however the Pfannenstiel group had a trend for better strength.

Remember, “Most clinicians use the scalpel as little as possible, opening layers bluntly”[26] instead. Blunt means that the surgeon will use his or her fingers to pull the incision apart once the initial incision has been made, thereby producing a diastasis recti.

Research so far indicates that the blunt technique has been associated with shorter operating times[27], and less injury to the tissues[28], including maternal blood loss[29]. Just to be clear, regardless of whether the tissue is expanded via cutting versus blunt technique, damage is still being done to the tissues, and therefore core muscle function and postpartum recovery are still the appropriate focal points.

When Can You Start Exercising After a C-Section?

- As soon as you are aware enough to do so, mild forms of gentle lying down inner core rehabilitation, like diaphragmatic breathing, and gentle core muscle re-integration should be performed, while in bed rest, asap.

- As soon as you are sitting up out of bed, sitting, standing and walking, additional gentle inner core exercises (that reinforce the activities of daily life that you are already doing) can be added within days.

- As soon as you have established proper inner core muscle function, more “normal” exercise programs can be resumed, in a logical manner that progresses from isometric (still) to slow primal movements and eventually back to faster movements. The key here is that returning to “normal” exercise should be done after you have learned how to activate the correct inner core muscles at the correct times. This could be as little as a couple weeks, or years and years (or never) for those who never rehab effectively.

The reality is that immediately after a C-section, you will use your muscles to sit up out of bed, stand, walk, sit, and hold your baby, therefore you are already technically “exercising mildly” whether you think you are or not. If you want to ensure that you are using the correct muscles when you do these instantly-required activities of daily life, you must either already know how to use your core muscles, or you need someone to teach you. (Some countries already provide standard postpartum recovery care for all births.)

The reason why this question is so often confusing is because everyone has a different definition of what exercise is. Doctors, who are not exercise professionals, need to make sure that their patients do not overdo it, so they create rules like: not for 6 weeks. They need to make sure that you don’t jump back into high-intensity exercise, and they don’t have the time or expertise to teach you how to re-integrate your inner core muscles.

The problem with being cleared for exercise after a certain time-frame is that it still doesn’t account for the fact that nearly everyone needs to set an appropriate postpartum recovery foundation first. Returning to typical exercise programs at 6 weeks, or even 12 or 18 weeks, when you haven’t learned appropriate core function, is far worse than starting appropriate gentle postpartum exercise program recovery as early as day #1. This is the type of advice that makes postpartum women look back decades later and feel like they never really recovered.

In part, this is because when any birthing person goes from pregnant to not pregnant in the course of a day (as all pregnancies & deliveries do), your muscles must immediately begin re-wiring to the new body. It is a massive difference to no longer have a tummy filled with a baby. There are natural levels of pressure-stability present in a pregnant body, which instantly disappears in the postpartum body. The requires an instantaneous physiological re-programming for every muscle in the postpartum body, just to be able to stand, move, etc.

If you want to reprogram well, you need to start being present with your muscles immediately.

In addition, a C-section demands a whole new muscle re-integration program as well. Cutting muscles means they are injured and need to relearn how to work functionally with the rest of the body.

If you’re reading this from your hospital bed now, fresh off your C-section, start by mindfully and gently doing this:

- Mindfully & gently INHALE into your ribs & belly. Feel for how this makes your C-section feel. Do not inhale so much that you put unnecessary pressure on your stitches. However, it will help your healing immensely if you (A) get fluids and inflammation to move, and (B) allow for a gentle tug to remind your wound which direction to start laying new collagen tissue (which could also help reduce the thickness of the C-section scar). If this inhale feels intuitively like it’s too much, then just try it again in another couple days.

- EXHALE in a manner that mindfully & gently helps you feel how that exhale affects your abdominal wall. The act of slowly extending the length of your exhalation by a few seconds, while placing your attention into this area of your body, not only begins informing your body how to re-connect your core muscles to their new situation, but also continues to provide a foundation for moving intrinsic healing chemistry into and out of the area. If this exhale feels intuitively like it’s too much, then just try it again in another couple days.

- Mindfully & gently add a pelvic floor contraction to your exhalation, feeling for how this muscle affects your C-section scar area. For 9 months or so, there was a lot of pressure forcing down into your pelvic floor muscles, which are primary inner core muscles that are on the same neurological pathways as your lower abdomen. Using your mind to re-connect these muscles will directly help your neurological system to re-connect with your lower abdomen, as well as reinforce proper core muscle function for the future.

- When you do start rolling over, sitting up, standing and more, mindfully & gently bring the above forms of “core breathing” with you. The initial foundational key to getting back to a core exercise program after a C-section is being present with these critical core muscles as soon as you possibly can!

Post C-section, postpartum recovery via an appropriate core exercise program is necessary to restore proper function to the abdominal wall. Multiple muscles show that multiple layers of tissue are cut during a C-section, although some muscles will be cut at their tendinous sheaths, or endpoints, rather than across the belly of the muscle.

Regardless of the terminology used when describing a C-section, trauma to the abdominal wall is the result, and appropriate muscular reconditioning is essential for the well-being of postpartum women.

We are now offering FREE ONLINE (ZOOM) WEEKLY GROUP FITNESS sessions. Register here!

If you are pregnant or postpartum and interested in Personal Training Sessions with Fit For Birth certified coaches, you can find out more here! At Fit For Birth, you can train with pre & postnatal fitness experts who know how to assess the pre-postnatal body and who will create safe, effective, fun, and individualized workout programs to help you have a strong pregnancy, delivery, and recovery. Our training programs are 100% virtual so you can train from anywhere in the world!

Click here for a continuation of this article that goes deeper into the various C-section techniques and further discusses the muscles and fascia that are cut.

If you are a Fitness or Wellness Professional, check out our courses and membership program here!

[1] https://symmetryptaustin.com/healing-expectations-for-different-tissue-types/#:~:text=Tendon%20Healing%20Considerations&text=Tendons%20generally%20have%20a%20more,tension%20on%20the%20tendon%20tissue.

[2] https://research.cornell.edu/news-features/tendons-injuries-and-healing

(Cornell Research Site)

[3] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.00336/full(2019, Frontiers in Physiology.)

[4] (2019) https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326858#injuries

[5] https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/muscle-pain-it-may-actually-be-your-fascia

[6] https://www.pelvichealing.com/treatment/scar

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4315586/

[8] https://obgyn.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2511§ionid=206170950

[9]Aponeurosis is defined by Britannica as: “a flat sheet or ribbon of tendonlike material that anchors a muscle or connects it with the part that the muscle moves.” https://www.britannica.com/science/aponeurosis

[10] https://gynecolsurg.springeropen.com/articles/10.1007/s10397-010-0560-9

[11] https://gynecolsurg.springeropen.com/articles/10.1007/s10397-010-0560-9

[12] https://obgyn.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2511§ionid=206170950

[13] https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00500-4/fulltext

[14] https://www.stepwards.com/?page_id=3610

[15] https://www.stepwards.com/?page_id=3610

[16] https://www.stepwards.com/?page_id=3610

[17] https://www.stepwards.com/?page_id=3610

[18]https://thedaisyfoundation.com/the-uterus-5-reasons-to-shout-about/#:~:text=By%20weight%2C%20the%20uterus%20is,that%20can%20birth%20a%20baby.

[19] https://www.livescience.com/32823-strongest-human-muscles.html

[20] https://www.loc.gov/everyday-mysteries/biology-and-human-anatomy/item/what-is-the-strongest-muscle-in-the-human-body/

[21] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546707/

[22] https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/3/3/14792174/half-scientific-studies-news-are-wrong

[23] https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00500-4/fulltext

[24] https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00500-4/fulltext

[25] https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00500-4/fulltext

[26] https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00500-4/fulltext

[27] https://gynecolsurg.springeropen.com/articles/10.1007/s10397-010-0560-9

[28] https://gynecolsurg.springeropen.com/articles/10.1007/s10397-010-0560-9

[29] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23123380/