Last updated 10/17/23

This article has the following outline. Feel free to jump to whatever information you’re seeking!

- Understanding the basic phases and hormones associated with the menstrual cycle

- Studies showing how the menstrual cycle may affect exercise performance

- Studies showing how menstrual cycles may affect injuries

- Studies showing how the exercise affects menstrual pain & symptoms

1) Phases and hormones associated with the menstrual cycle

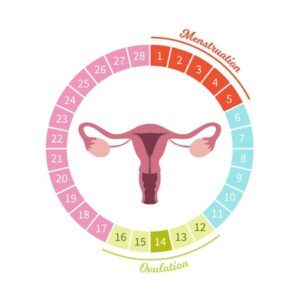

There are actually two cycles that are tightly coordinated and commonly referred to as the menstrual cycle. The Uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the uterine lining to receive an embryo. The Ovarian Cycle governs the preparation of endocrine tissues and the release of eggs.

These are typically discussed in two stages, before and after ovulation (egg release from the ovary): Follicular Phase (FP) and Luteal Phase (LP).

First Half: Before Ovulation is what’s called the Follicular or Proliferative Phase (FP). The follicular phase, typically lasting around 14 days, begins on the first day of menstruation bleeding. The normal range of menstrual flow is considered to be 2 to 8 days. Bleeding occurs as layers of the thickened lining of the uterus break down and are shed, because the last ovarian cycle did not produce a pregnancy, and therefore there is no need to have the extra nutritive cells required for providing nutrition and successful implantation. The remaining portion of the follicular phase is when there is new development of ovarian follicles, which are fluid-filled sacs that contain immature eggs. This phase can be further split into the Early Follicular Phase and Late Follicular Phase, indicating, respectively, the first day of the cycle until estrogen increase begins, and estrogen increases through preovulatory estrogen peak.

Hormonally, FP is dominated by FSH and rising estrogen levels. Here is an overview:

- FSH: Follicle-Stimulating Hormone. FSH stimulates the growth of follicles (the small sacs containing immature eggs).

- Estrogen: Levels gradually rise in the midst of this phase, and then will drop precipitously at ovulation. As the follicles increase in size, they begin to release estrogen (primarily in the form of estradiol).

- Progesterone: As the follicles increase in size, they begin to release a low level of progesterone.

- LH: As the dominant follicle matures, it releases increasing amounts of estradiol, which leads to a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH). This surge in LH triggers ovulation, the release of a mature egg from the ovary. The frequency and amplitude of LH secretion during the follicular phase (FP) regulate subsequent luteal phase (LP) function. The LH surge indicates the end of the Follicular Phase.

- HCG: May overlap with LH to support the stimulation of follicle maturation and induction of ovulation

- Note: An IVF “trigger shot” of HCG can help the ovaries to mature and release eggs

- Relaxin: Levels remain relatively low

Midpoint: Ovulation is when a mature egg is released from the ovary, into the fallopian tube, where it can be fertilized by sperm. Ovulation causes the formation of a temporary but vital organ that plays a crucial role in fertility during the upcoming Luteal phase (LP). After ovulation, the ruptured follicle transforms into a structure called the corpus luteum. (During ovulation, an egg is released from a dominant follicle. After the egg has left the follicle, the corpus luteum starts to form from the materials that make up that follicle.) The corpus luteum exists within the ovary once the ovarian follicle has released a mature egg during ovulation. Its job is to produce hormones (progesterone and relaxin) that support pregnancy and childbirth. If the egg produced is fertilized, the progesterone production from the corpus luteum continues for several weeks. Without fertilization, the corpus luteum stops working in a few days and withers away.

Second Half: After Ovulation comes what is called the Luteal or Secretory Phase (LP). This phase comes after the mature egg is released and before the next cycle of period bleeding. It is a preparation phase for a possible pregnancy and lasts about 14 days for most women. It is marked by the presence of the corpus luteum and the eventual decline in hormones if pregnancy does not occur.

Hormonally, LP is dominated by progesterone, with some estrogen. Here is an overview:

- Progesterone: The Corpus Luteum secretes progesterone, to help maintain the uterine lining, making it receptive to a potential embryo for implantation. Progesterone will also peak in the middle of this phase, before rapidly declining later, as menstruation once again nears. Secretion is episodic, also correlating closely with pulses of LH secretion.

- Estrogen: After dropping post-ovulation, estrogen levels will then undergo a secondary rise in the middle of the LP phase. Secretion is episodic, correlating closely with pulses of LH secretion.

- NOTE: The increase in estrogen and progesterone levels cause milk ducts in the breasts to widen. As a result, the breasts may swell and become tender.

- FSH: Levels decrease during the luteal phase.

- LH: Levels decrease during the luteal phase.

- HCG: May support a rise in progesterone during the early luteal phase.

- If fertilization and implantation occur, the developing embryo releases human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which signals the corpus luteum to continue producing progesterone. This hormone is crucial for sustaining pregnancy.

- Relaxin: Relaxin levels are the highest during this second half of the monthly cycle, as levels rise to prepare the body for a possible pregnancy.

If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum gradually breaks down, leading to a drop in progesterone and estrogen levels. This hormonal decline triggers the shedding of the uterine lining, once again resulting in menstruation. Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) refers to a collection of physical and behavioral changes that certain women undergo in the lead-up to their monthly menstrual periods.

2) How the Menstrual Cycle May Affect Exercise Performance

A whole bunch of recent studies have weighed in on how menstruation may affect exercise performance. The short answer is that although anecdotal evidence exists all around, there is no valid scientific evidence to support that menstruation has a consistently significant effect. Ultimately, researchers suggest taking an individualized approach.

Here are some specific studies you can check if you’d like:

2020 – A study of 15 rugby players found that 93% reported menstrual cycle-related symptoms and that 67% considered these symptoms to impair their performance.

2020 – A study of 140 biathlon or cross-country skiers found that most athletes reported their worst fitness and performance, as well as the highest number of side effects during the bleeding phase of their cycle (the first part of FP). The phase following bleeding (late follicular phase) was considered the best phase for perceived fitness and performance

2020 – A systematic review and meta-analysis of 78 studies found that exercise performance “might be trivially reduced” during early follicular bleeding. Authors concluded that it is not wise to form general guidelines on exercise performance, and recommended instead that a “personalized approach” based on each individual’s response should be the guiding principle.

2023 – A study of 12 French rowers found that women with a natural cycle (not using hormonal contraception) find their performance and wellness to be significantly higher in the middle of their cycle (near ovulation). (This study also found that those who use hormonal contraception find that they perform better while using the medication, compared to those not regulating with pills.) Performance levels in this study were also secondarily correlated by their coaches’ evaluations.

2023 – A study of 26 women with “healthy normal” menstruation found that there was “no difference in physical performance” between FP and LP (at any time before or after ovulation).

2023 – A second Systematic Review, this time on resistance exercise training found it to be once again “premature to conclude any appreciable influence” of menstruation on exercise performance or strength or muscle size development.

2023 – Lastly, a commentary article suggested how the wide variation of menstrual symptoms makes it difficult to suggest a proper exercise program, and agreed that future research must instead “consider individual variations.”

3) How Menstrual Cycles May Affect Injuries

There is little question that women and girls experience more injuries playing sports, compared to their male counterparts. However, although female reproductive hormones are known for being associated with changes like ligamentous laxity, evidence shows that it is not the menstrual cycle that is the injury-causing factor. The causative factors may have more to do with health & mindfulness factors—which can happen to disrupt regular menstruation—but which then lead to injury. These health & mindfulness factors include things like restrictive eating, eating disorders in general, overtraining, and even the lack of menstrual periods altogether.

Here are some specific studies you can check if you’d like:

2021 – A study on 846 female athletes representing 67 different sports found that although athletes were more likely to miss participating due to menstrual dysfunction, it was eating disorders and restrictive eating that were associated with getting injured.

2021 – A study on 101 women with bone stress injuries discovered that women with more of these injuries were those whose menstrual cycle was absent altogether. Authors concluded that “maintaining normal menstrual status during adolescence and young adulthood may reduce the risk of multiple bone stress injuries.”

2023 – A systematic review that included only 7 of 418 articles (due to what they determined to be an overall poor quality of studies), found it to be inconclusive whether or not any particular portion of the menstrual phase predisposes women to risk of injuring their ACL (a common knee ligament injury).

2023 – Lastly, a study on female athletes discussed how ACL knee ligament ruptures, knee pain in general, ankle sprains, and bone stress injuries are far more frequent in females than in males. Although female reproductive hormones are a differentiating factor between the sexes, authors wrote that it is really, “Insufficient diet and intensive training [that] can lead to menstrual irregularities…and result in injury.” These authors also noted that oral hormonal contraception may have a protective effect against certain injuries.

How Exercise Affects Menstrual Pain & Symptoms

In a reversal of causality, I wanted to see whether or not any research had been done to discover whether or not a basic health foundation, like exercise, might affect a wellness indicator like the quality of menstruation. After all, hormones and internal chemistry are what physically drive the menstrual cycle, and exercise can powerfully affect one’s ability to regulate her hormones and internal chemistry. And it turns out that research does show that women and girls who exercise do indeed experience fewer adverse menstrual cycle symptoms, like less mood swings, bloating, irritability, fatigue, and pain!

Here are some specific studies you can check if you’d like:

2006 – A study of high school girls -found that exercise can decrease the severity and duration of pain associated with menstruation. Authors in this study explained what they thought were the reasons why: Menstrual discomfort likely arises from heightened contractions of the uterine muscle, which receives nerve signals from the sympathetic nervous system. Stress tends to intensify this sympathetic activity and, as a result, can worsen menstrual discomfort by amplifying uterine contractions. Exercise, on the other hand, may reduce sympathetic activity by alleviating stress, thus mitigating these symptoms. In addition, exercise is recognized for triggering the release of endorphins, natural brain-produced substances that elevate the body’s tolerance for pain.

2021 – A study of 128 women first classified each as an “avoider” or a “nonavoider” of physical activity “due to menstrual events.” Those who tended to avoid exercise near menstruation reported “longer periods, heavier menstrual flow, and higher levels of fatigue and pain” compared with those who made the effort to exercise.

2023 – Finally, A Narrative Review (a comprehensive, critical, and objective analysis of the current knowledge on this topic) found that it’s worth reaching for exercise over drugs for managing PMS symptoms! Specifically, the authors wrote, “The management of PMS traditionally involves pharmacological interventions; however, emerging evidence suggests that exercise may offer a valuable non-pharmacological approach to alleviate PMS symptoms.” The study confirmed that engaging in consistent physical activity has been linked to a decrease in both physical and psychological symptoms commonly experienced during PMS, such as discomfort, tiredness, mood fluctuations, and fluid retention. Moreover, exercise has shown promise in improving overall quality of life and counteracting the adverse impacts of PMS on everyday activities and well-being.

Conclusion

Studies indicate that the female uterine/ovarian/menstrual cycle appears to be honed to provide the least amount of detraction from her physical abilities, in terms of both performance and injury. This appears to be especially true if the girl or woman honors her foundational wellness principles, like healthy eating habits and continuing to exercise even when the discomfort of PMS arises, whenever possible. Still, the best approach will always be for you to remember that you are a unique individual. Listen to your body, and develop your intuition for knowing when to push harder and when to rest a bit more.

If you would like personalized fitness training that considers who you are as a unique individual, there is no better place than Fit For Birth certified trainers! Reach out to discuss training options with one of our Head Coaches today! (And make sure to check if one of our weekly FREE ONLINE GROUP TRAINING Sessions matches your schedule!)

REFERENCES

Bischof, P. The Menstrual Cycle. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved 10/17/23 from https://www.gfmer.ch/Presentations_En/Menstrual_cycle/Menstrual_cycle_Bischof.htm

- Findlay RJ, Macrae EHR, Whyte IY, et al. How the menstrual cycle and menstruation affect sporting performance: experiences and perceptions of elite female rugby players. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:1108-1113. Retrieved 10;15;23 from https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/54/18/1108.info

- Solli, et al. Changes in Self-Reported Physical Fitness, Performance, and Side Effects Across the Phases of the Menstrual Cycle Among Competitive Endurance Athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijspp/15/9/article-p1324.xml?content=contributor-notes

- McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, Thomas K, Hicks KM. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020 Oct;50(10):1813-1827. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3. PMID: 32661839; PMCID: PMC7497427. Retrieved 10/15/23 from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32661839/

- Antero, et al. Menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptive phases’ effect on elite rowers’ training, performance and wellness. Frontiers in Physiology. Retrieved 1016/23 from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2023.1110526/full

- de Carvalho, G., Papoti, M., Rodrigues, M.C.D. et al. Interaction predictors of self-perception menstrual symptoms and influence of the menstrual cycle on physical performance of physically active women. Eur J Appl Physiol 123, 601–607 (2023). Retrieved 10/15/23 from https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-022-05086-z

- Colenso-Semple, et al. Current evidence shows no influence of women’s menstrual cycle phase on acute strength performance or adaptations to resistance exercise training. SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article. Front. Sports Act. Living, 23 March 2023

Sec. Elite Sports and Performance Enhancement. Volume 5 – 2023 | Retrieved 10/15/23 from https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1054542

- Prado RCR, Kilpatrick MW. Menstrual Cycle and Performance: What Is Next? Sports Health. 2023;0(0). Retrieved 10/15/23 from doi:10.1177/19417381231197609

- Ravi, et al. Self-Reported Restrictive Eating, Eating Disorders, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Injuries in Athletes Competing at Different Levels and Sports. Nutrients. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/9/3275

- Rudolph, et al. Physical Activity, Menstrual History, and Bone Microarchitecture in Female Athletes with Multiple Bone Stress Injuries. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8440446/

- Dos’Santos, et al. Effects of the menstrual cycle phase on anterior cruciate ligament neuromuscular and biomechanical injury risk surrogates in eumenorrheic and naturally menstruating women: A systematic review. PLOS ONE. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0280800

- Raj RD, Fontalis A, Grandhi TSP, Kim WJ, Gabr A, Haddad FS. The impact of the menstrual cycle on orthopaedic sports injuries in female athletes. Bone Joint J. 2023;105-B(7):723-728. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.105B7.BJJ-2022-1262.R2 Retrieved 10/15/23 from https://boneandjoint.org.uk/article/10.1302/0301-620X.105B7.BJJ-2022-1262.R2

- Z Abbaspour, M Rostami, Sh Najjar. The Effect of Exercise on Primary Dysmenorrhea. J Res Health Sci. 2006;6(1): 26-31. Retrieved 10/15/23 from https://jrhs.umsha.ac.ir/Article/305

- Kolic, et al. Physical Activity and the Menstrual Cycle: A Mixed-Methods Study of Women’s Experiences. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/wspaj/29/1/article-p47.xml

- Sanchez, et al. Premenstrual Syndrome and Exercise: A Narrative Review. MDPI. Retrieved 10/16/23 from https://doi.org/10.3390/women3020026

—————————————————-

James Goodlatte is a Father, Holistic Health Coach, Corrective Exercise Practitioner, Speaker, Author, Professional Educator, and the founder of Fit For Birth. In 2008, He found out he would be a father and immediately shifted his passion for holistic wellness and fitness to his family. Today, he is a driving force in providing Continuing Education Credits for the pre and postnatal world, with Fit For Birth professionals in over 50 countries. James is also the program director for Fit For Birth pre & postnatal personal training worldwide, and is a contributing member of the First 1000 Days Initiative at the Global Wellness Institute.