A viral Instagram post shows a split image of a mother lifting weights during pregnancy, and then her seemingly muscular newborn. The caption says, “This mom lifted weights through pregnancy: Check out her ‘buff’ baby!”[1] A few days later, the highest trending comment with the most likes was one that discounted the connection between exercise and infant body type, saying, “Come on people…we know that’s not how it works.”

Actually, that is how it works.

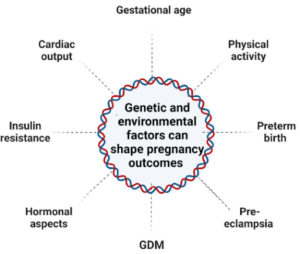

And yes, the profound legitimate impact on newborns is increasingly what scientific evidence in epigenetics continues to reveal, even as many people remain oblivious. At this point, many parents have a general sense that the mom’s health affects the baby’s health, but it goes way deeper than that. Our health – both moms and dads – at the time of conception and over the course of pregnancy, is constantly generating epigenetic changes that profoundly affect their baby (for better and for worse).

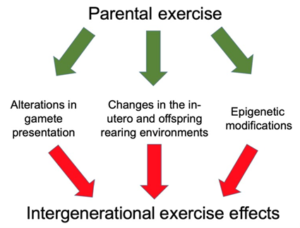

In fact, it’s far bigger than you may have been led to believe, as epigenetic adjustments in the parents are now being found to pass “transgenerationally” to their children, seemingly having effects on their children’s own foundations for their lifelong genetic health.

Quickly Understand Epigenetics in 5 Steps:

- We do something: think, exercise, eat, sleep, etc in some manner.

- How we perform these things causes our DNA to produce a certain kind of chemistry inside the cellular environment (essentially having to deal with, or manage, whatever the stimulus was).

- This internal chemistry not only works toward managing things but also lingers nearby, affecting the cellular environment enough to turn certain genes on or off.

- This new genetic “on and off” then produces new/additional chemistry, which reinforces existing gene expression and/or also further alters which genes are kept on or off.

- And the cycle continues with every movement we do (or don’t do), every bite we take, every time we sleep (or don’t), and with every thought that emotionally shifts our internal chemical environment.

Exercising during pregnancy – as well as enacting any other health improvements that inspire you – could be the best lifelong gift you’ll ever give to your child. Check out what a 2019 systematic review in Physiological Reports wrote: “The evidence suggests that exercise‐induced epigenetic changes can be observed in offspring and may play a pivotal role among the multifactorial intergenerational‐health impact of exercise.”[2] Even more, the epigenetic DNA changes that do occur during pregnancy (exercise or otherwise) have been shown to persist into childhood![3]

Four specific examples in which exercise (and other health factors) can genetically affect parents and offspring.

1. Moms who exercise during pregnancy (and dad’s prior to conception) mitigate the negative effects of unhealthy diets’ effects in their children. A 2021 examination in the Journal of Applied Physiology looked at whether running could negate the adverse effects of an unhealthy high-fat diet in both male and female mice parents. Researchers looked at whole genome DNA methylation analyses of PGC-1α. The conclusion was that high-fat diets would negatively influence the offspring’s metabolic outcomes later in life, but that moms that exercise during pregnancy would reduce the severity of any negative effects.[4]

2. Fathers who exercise affect gene expression in their children. A 2022 study on mice in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, found that paternal exercise affected the H19/IGF2 gene location, affecting gene expression in the skeletal muscle of the offspring. Authors wrote how remarkable the evaluation of the paternal sperm was, “indicating that exercise-induced epigenetic changes that occurred during germ cell development contributed to transgenerational transmission.”[5] Their conclusion was that exercising dads, prior to conception, should be considered as a strategy to promote metabolic health in the offspring, and that these results would be inherited transgenerationally.

3. Mothers with gestational diabetes (GDM) can re-balance their gene expression by exercising. A mother who has GDM will show epigenetic reductions in IGF2 and H19 genes (which affects insulin sensitivity).[6] A reduction of IGF2 reduces other helpful genes, like SIRT1 (a longevity gene associated with numerous health functions[7]) and PGC-1α (remodels muscle tissue[8]), but IGF2 increases after exercise training.[9]

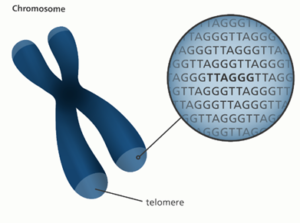

4. Mothers who exercise and more effectively manage stress pass stronger DNA to their offspring (via telomere length). A 2022 systematic review in Medicina showed that although telomeres are longer in those who are generally active, rather than inactive, aerobic exercise for more than 6 months (ranging from 20-60min 3-5x week at various intensities) showed the most significant “positive improvement” on telomere length.[10] Oxidative stress reduction was the mechanism identified for this epigenetic change. Telomeres are the “bumpers”[11] at the end of each chromosome, the protective ends of the DNA that ensure the appropriate full DNA sequences are transferred to the next cell when dividing. “Because of direct transmission, both parents’ telomeres – at whatever length they are at the time of conception in the egg and sperm – are passed to the developing baby (a form of epigenetics)…regardless of genetics.”[12] Other areas scientifically proven to be passed from parent to child in the form of shortened telomere length, include: low education level, living in a dangerous neighborhood, “severe stress and anxiety,” smoking, low protein diet, and inadequate folate.[13] “Mothers with the highest number of stressful life events had babies with telomeres that were shorter by 1,760 base pairs at birth.”[14]

What kinds of things should I be aware of as having an epigenetic influence on me and my baby?

- “Generally, it has been shown that acute and long-term exercise has a significant effect on DNA methylation, an important aspect of epigenetic modifications.”[15]

- “Although diet, genetic predisposition, and a healthy lifestyle seem to alter DNA methylation and telomere length (TL), recent evidence suggests that training status or physical fitness are some of the major factors that control DNA structural modifications. In fact, TL is positively associated with cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity level (sedentary, active, moderately trained, or elite), and training intensity.”[16]

- “Maternal nutrition, tobacco smoking, ambient and household air pollution, and traffic-related air pollution during early development were risk factors associated with epigenetic changes in LMICs [low- and middle-income countries]. In particular, the HDAC, HAT, and GNAT families (groups of proteins involved in the regulation of gene expression), specifically, were associated with lung health outcomes.”[18]

- “Nutrition is one of the most studied and better understood environmental epigenetic factors…suggesting that effects may persist and impact our children and even beyond. It seems likely that the fetus epigenetically adapts in response to a limited supply of nutrients. In humans, persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine have been ascribed to a lower degree of methylation of a gene implicated in insulin metabolism than their unexposed siblings.”[19]

- Practicing “mindfulness and compassion meditation, revealed that the epigenetic aging rate in meditators is significantly decreased,” as well as affects methylation regions corresponding to at least 43 genes involved in immune metabolism, glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, protein folding, neurotransmission, and modulation of inflammatory pathways (more rapidly for experienced meditators).[20]

- “Telomeres tend to be shorter with negative thinking. But they may be stabilized or even lengthened by practicing habits that promote stress resiliency.”[21] Factors making up stress resiliency include practicing: meditation, being present, being conscientious, waking joyfully, self-compassion, feeling purpose, adopting a challenge-response (rather than defeatism), and self-discipline.

So what about that viral IG post?

One of the top replies to “Come on people…we know that’s not how it works” was “So many women are going to try this because they think this fraudulent video is real and that their babies will have muscles when they’re born. Spreading misinformation like this is going to lead to miscarriages and stillbirths.”

This lit a bit of a fire within group discussion within Fit For Birth’s Holistic Fertility & Pregnancy Safe Coach professional community group discussion as one coach, Juliet Grey, wrote, “I was so surprised to see that people weren’t inclined to believe that maternal workouts would also positively impact baby…I feel that people’s perception that this couldn’t be the case also shows how we look at pregnancy. We don’t really see mother and baby as connected and symbiotic as they are.” This pre-postnatal fitness professional went on to lament our current cultural reality that “shows the challenges we face trying to reveal the reality of pregnancy to our clients, and how their health is connected to their babies health…”

Thankfully, however, another comment appeared as the second most viral trending mention to that Instagram post, in an effort to balance the inaccuracy of the prior. It was another Fit For Birth Holistic Fertility & Pregnancy Safe Coach, Maggie Yount, who disclosed the truth, “Baby muscles or not, working out during pregnancy is GREAT for mom (assuming a healthy, normal pregnancy) and research has shown that a fit mom = a fit baby. Higher APGAR scores, lifting their head sooner, etc. It does not increase the risk of miscarriage.”

References

[1] Retrieved 1/7/23 from https://www.instagram.com/p/CoID67WLOLZ/?igshid=NDk5N2NlZjQ=

[2] 2019. Axsom & Libonati. Impact of parental exercise on epigenetic modifications inherited by offspring: A systematic review. Physiological Reports. Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6874781/

[3] 2021. Herbstman, et al. Predictors and Consequences of Global DNA Methylation in Cord Blood and at Three Years. PLOS ONE. Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0072824

[4] 2021. Laker, et al. Exercise during pregnancy mitigates negative effects of parental obesity on metabolic function in adult mouse offspring. Journal of Applied Physiology. Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00641.2020

[5] 2022. Costa-Junior, et al. Paternal Exercise Improves the Metabolic Health of Offspring via Epigenetic Modulation of the Germline. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8744992/

[6] 2019. Mambiya, et al. The Play of Genes and Non-genetic Factors on Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in Public Health. Retrieved 2/7/23 from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00349/full

[7] 2019. Kim, et al. Knockout of longevity gene Sirt1 in zebrafish leads to oxidative injury, chronic inflammation, and reduced life span. PLOS ONE. Retrieved 2/7/23 from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220581

[8] 2006. Liang, Huiyun. Ward, Walter. PGC-1alpha: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Advances in Physiology Education. Retrieved 2/7/23 from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17108241/

[9] 2021. Zhu, et al. IGF2 deficiency causes mitochondrial defects in skeletal muscle. Clinical Science (London, England: 1979). Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8055961/

[10] 2022. Song, et al. Does Exercise Affect Telomere Length? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina (Kaunas). Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8879766

[11] Telomeres are more technically the TTAGGG repeats at the end of each chromosome.

[12] 2018. Blackburn & Epel. The Telomere Effect: A revolutionary approach to living younger, healthier, longer. Book. Orion Publishing Group Ltd.

[13] 2018. Blackburn & Epel. The Telomere Effect: A revolutionary approach to living younger, healthier, longer. Book. Orion Publishing Group Ltd

[14] 2018. Blackburn & Epel. The Telomere Effect: A revolutionary approach to living younger, healthier, longer. Book. Orion Publishing Group Ltd

[15] (n.d.) Epigenetics of physical exercise. WIkipedia. Retrieved 12/14/22 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigenetics_of_physical_exercise

[16] 2021. Sellami, et al. Regular, Intense Exercise Training as a Healthy Aging Lifestyle Strategy: Preventing DNA Damage, Telomere Shortening and Adverse DNA Methylation Changes Over a Lifetime. Frontiers in Genetics. Retrieved 12/14/22 from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.652497/full

[17] 2019. Axsom & Libonati. Impact of parental exercise on epigenetic modifications inherited by offspring: A systematic review. Physiological Reports. Retrieved 12/13/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6874781/

[18] 2019. Robertson, et al. The role of epigenetics in respiratory health in urban populations in low and middle-income countries. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics. Retrieved 12/14/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6983949/

[19] 2019. Tiffon, Celine. The Impact of Nutrition and Environmental Epigenetics on Human Health and Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Retrieved 12/14/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6275017/

[20] 2020. Venditti, et al. Molecules of Silence: Effects of Meditation on Gene Expression and Epigenetics. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved 12/14/22 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7431950/

[21] 2018. Blackburn & Epel. The Telomere Effect: A revolutionary approach to living younger, healthier, longer. Book. Orion Publishing Group Ltd.